Lately I’ve seen more cellphones in late 1990s movies than recent releases, a fact almost completely at odds with historical reality.

Perhaps that’s because back in the 1990s, movies were *excited* about global telecommunications possibilities. That was before these ubiquitous small-screen devices, now used everywhere from Antarctica to Zambia, became a kind of competitor to the Big Screen.

Once upon a time, you couldn’t just talk to anybody anywhere. I am old enough to remember then; maybe you are, too. That possibility was found only in the domain of science fiction. Kirk telling Scotty to “beam me up,” from any spot on any planet, seemed impossible.

But in 1973, the first cellphone was used, April 3rd to be exact. Big players you may know — Motorola and Bell Labs — were involved in this supposedly promising development.

At the same time, another astounding act of impossible communication was taking place: the launch of Voyager 1. That was in the same year as the first Star-Wars movie, 1977, with a massive act of quixotic delusion that both delights me and makes me chortle.

On Voyager 1 is a gold record, an attempt to actually contact any intelligent being — Martians or Wookies — who could access it. From American scientists, this was astoundingly hopeful gesture: that intelligent communication can cross planetary and galactic boundaries. That E.T. could hear and respond to a human language, maybe all of them.

I mention these two historical events in the mid-to-late 1970s because my current, tentative excursion into this topic makes me think that a strong lust for global telecommunications, the breaking of all boundaries of language, the attempt to talk to anybody anywhere at any time, was a key part of the Zeitgeist then.

The spirit of the age, as it were, was “Close Encounters.”

You remember that 1977 Spielberg film: aliens communicate to people in dreams, then meet them on Devil’s Tower, playing a simple melody as an act of saying “hello!”

In that movie the entire world unites around the much-dreamed-of first-contact event. It’s a global dream: we communicate with aliens easily, which in my view can be interpreted as a metaphor for communicating with any human easily. “Close Encounters” has a global vision of speaking, listening, and understanding.

Along comes George Lucas. Like many great artists, he channels the ‘70s Zeitgeist, reflecting it at least, maybe also tweaking or critiquing it.

You might never have noticed it, but possibly no movie has lusted for human-human telecommunications, from anywhere on Earth or in heaven, at any time, than “The Empire Strikes Back.”

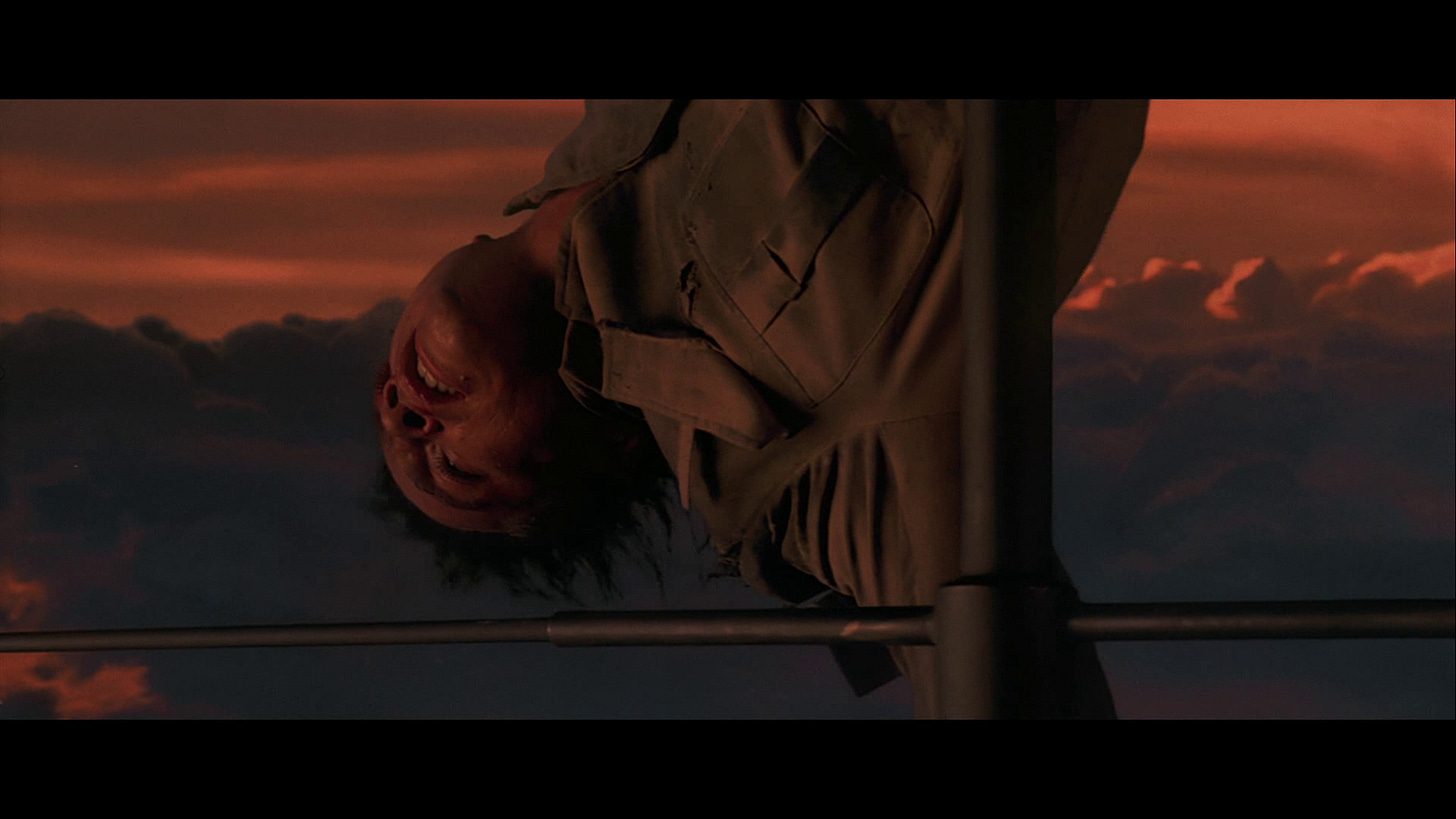

Let’s begin with Luke Skywalker’s near-fall to his death. At the end of “Empire,” he chooses the light-side of the Force and falls down a gas-mining tube, released as debris into a gas planet’s atmosphere.

The movie pictures him dangling from a structure that appears to me now like an upside-down piece of a cell tower.

I’ve long wondered why this always looked an antenna to me, the kind of object we used to put on structures to receive messages, such as through-the-air TV channels. Practically, this “antenna” keeps him from dying in the movie. But it doesn’t seem to be there for gas-mining, although what do I know about floating cities that mine xenon and helium?

While on this antenna structure, Luke uses the force to contact Princess Leia. He says the crucially phrased line, “hear me.” Not “help!” but a call to be heard.

He might as well be saying, “Do you hear me now?” She hears and responds, like her phone just rang with “hottie Luke” as her contact name for him.

This act of telepathy, common in science-fiction had pretty much washed out of the genre as a major plausibility by this point. Back in the ‘50s and ‘60s, science-fiction works routinely depicted humans as having the capacity for ESP.

By the ‘70s, though, that seemed likely hokey superstition. As in “Star Wars,” you need a mystical religion, Jedi-ism, to dream of ESP possibilities. It’s not a plausible physical possibility, just a New-Age dream.

But maybe it’s not just superstition. Here in “Empire,” Luke’s on an *antenna* of some kind. He’s communicating. He’s able to talk to his sister without a phone cord. She’s able to talk while riding in a vehicle. Such are science-fiction dreams.

Were this 2025, they’d be debating which Verizon plan they need.

The movie in particular *loves* this moment. It’s the most visual prominence given to Carrie Fisher’s character throughout the film. Otherwise, she’s depicted as an aristocratic imp, pictured as small throughout the entire film, placed down in the bottom-half of most frames that she appears in, a site of relative weakness and insecurity.

“Empire” has been building to this moment throughout its runtime. It has dozens of global and intergalactic acts of communication, in which the promise of any human talking to any human is completely fulfilled by the movie’s science-fantasy dreaming.

Moreover, the movie’s major plot shifts and tensions are predicated entirely on *losing contact* with people.

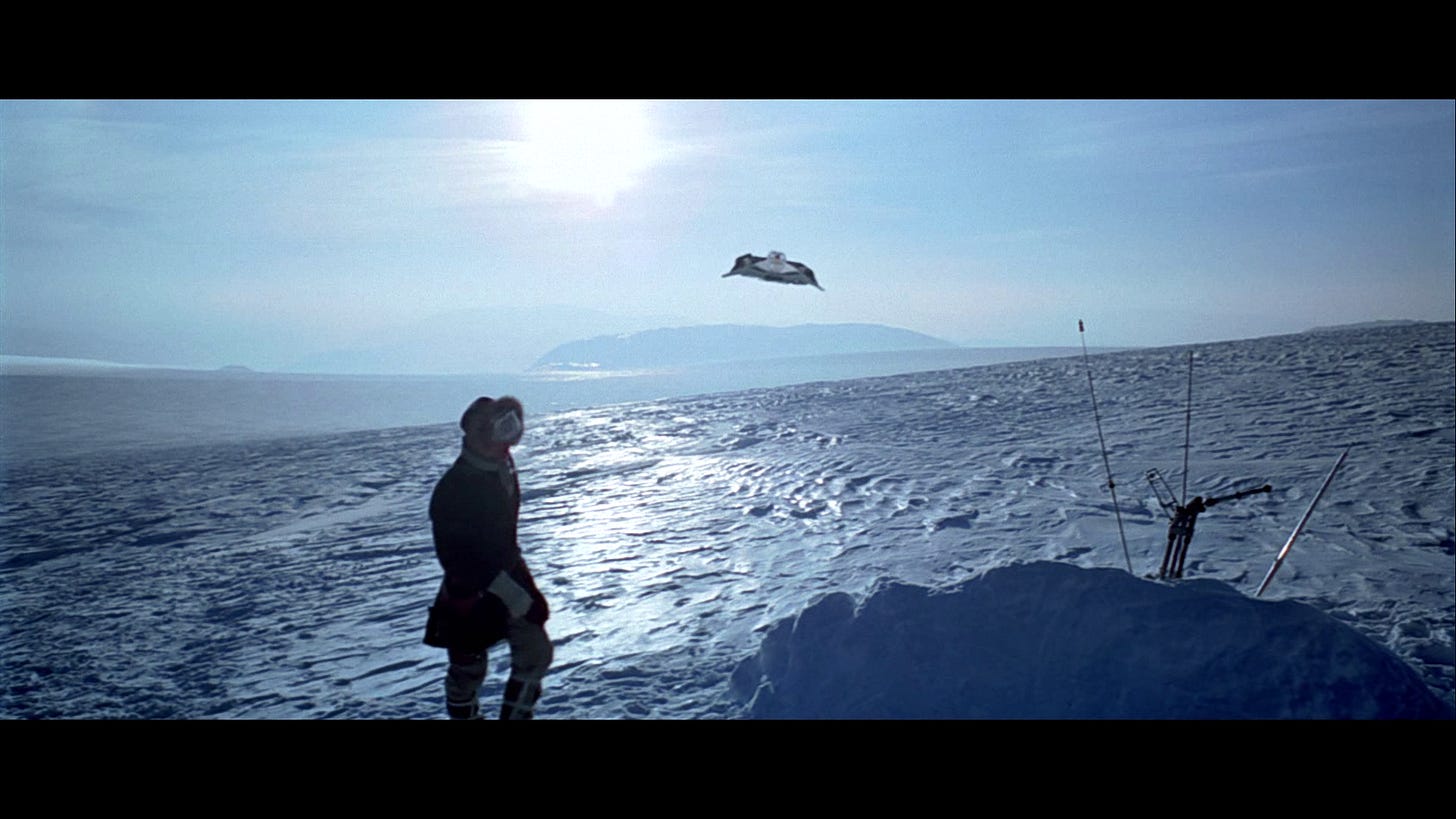

To wit, the movie opens with the Empire trying to find the Rebellion, effectively making contact with them. Not much later, Luke and Han Solo are lost in the blizzard on the ice planet. Luke calls out to Obiwan Kenobi to save him, who answers him from the realm of the dead, which might as well be video SnapChat.

Later, the Empire loses track of the Millennium Falcon. Luke loses contact with Leia and Han, and he worries about them after seeing their futures. Lost in the gas-mining colony, C3PO disappears, worrying Leia over lost contact with him.

Meanwhile, as Darth Vader is killing his commanders over video for failing him, other replacement officers worry about having contact with Vader. Hit the “mute” button quick, captains!

What all of these lost-contact scenarios need are the means of contact, which means instant telecommunications, anywhere at any time.

Telepathy works as such, though only if you have the Force. I view Force-telepathy metaphorically here, as yet another manifestation of the dream of ubiquitous telecommunications. Luke learns to talk to anybody almost as he pleases. Later “Star Wars” films, like Episode 8, extended this possibility to the extreme, during the cellphone-age of course.

If only Han Solo had a cellphone on Hoth. If only C3PO could ring up Chewbacca to tell him about the stormtroopers. If only Luke could phone Luke on Dagobah and tell him that everything’s alright! Otherwise, he worries too much, says Yoda. But Luke wants to talk to his sister, right now!

In “Empire,” most of the Lost-Contact moments are restored, except for Han Solo’s carbon-freezing, which is what the movie ends with: the promise that the sequel will restore lost contact between the rebel leaders and their old friend Han. He really needed a GPS tracker, badly, although maybe in space that acronym changes to “Galaxy Positioning System.”

All of this is in line with optimistic assumptions that plenty of American science-fiction at the time was predicated on. Just released a year before “Empire,” in 1979, the first “Star Trek” movie literally involved Voyager 1 recontacting humans after evolving into a massive super-intelligent spaceship. That film assumed that Voyager’s gold-record dream of talking to E.T. was beyond successful.

The best example of complete trust in alien-human communication through modern marvels remains Robert Zemeckis’ later movie “Contact,” from 1997 and based on a Carl-Sagan novel. In that one, humans quickly decode messages from space, build a mega-platform, and send an astronaut to contact aliens for the first time. The movie makes it all look relatively easy, including talking to aliens as if they’re your dear old dad.

Plenty of SF examples abound that criticize this communication optimism, many of them from behind the Iron Curtain. My favorite is Stanislaw Lem’s novel “His Master’s Voice,” in which a Manhattan Project-like team fails to figure out the seemingly intelligent signals they are getting from space, although they do find plenty of partial and mis- interpretations of the message. Lem’s “Solaris” and the Strugatsky Brothers’ great “Roadside Picnic,” on which Tarkovsky’s “Stalker” is based, make similar criticisms about the plausibility of communicating with any intelligent being from anywhere in the universe.

Because, after all, how do we even know what aliens are saying?

If we bring that science-fictional speculative question to 1970s tech possibilities, as I think “Empire” does, do we even want to talk to people around the world, any time, and any place? Maybe we have nothing to say to each other. Maybe it will be mundane. (This is more or less Thoreau’s mid-19th century criticism of the telegraph, the first global telecommunications technology.)

There is no frame of “Empire” that doesn’t say: “we must speak to each other from anywhere, whenever we want, because losing contact with each other is the worst possibility we can imagine!” Even losing contact with the Empire, which means losing contact with Daddy.

But there’s a qualification to my thesis. Machines, droids included, *shouldn’t be* the ones to communicate with us. And we shouldn’t want instant communication with them. All of the desired telecommunications in “Empire” is human-to-human. Sorry, chatbots, “Star Wars” has no time for you.

Take C3PO. A worrying chatterbox, they put their hands over his vocal box, they shut him off, and they even blow him to bits.

He, the humanoid robot, the AI with a golden body, is not the one you want to talk to long-distance.

Neither is R2, who can’t even speak your language. He gets fried late in the movie when he miscommunicates with a computer. Machines can fail to talk well or at all; they might deceive, like R2, or they might work for totalitarian evil, like the probe droid.

Instead, human communication, especially through the ultimate cosmic cellphone, the Force, is the ultimate goal.

That’s the communication network that interconnects families. In “Empire,” it causes . . . big gulp . . . a family reunion. (Am I supposed to say that the Force is like Verizon? Well, pick your favorite carrier!)

I’m working my way to the most famous scene in the movie: “I am your father.” That’s the line of lines to be said, the four-word phrase that must be delivered to the receiver. It’s delivered in person, perhaps because Vader hasn’t plugged Luke’s cell into his contacts.

I’m kidding there, but not exactly. These two have to meet in person, in a confrontation, but after that, they *do* have each other’s metaphorical cell numbers. This movie’s final act of interpersonal, intergalactic, impossible-communication across parsecs (jk, almost), is Luke and Vader saying “Father . . . Son” telepathically.

The metaphor is global communication. Because maybe one day, in reality, they will be able to say this to each other from anywhere, at any time.

In the 1980s, cellphones become a product. They start big and chunky, then get smaller. Nowadays, Luke might have his earbuds in, phone connected to Bluetooth.

“Father . . . can you hear me now?”