"Pi" Predicts A.I., then Criticizes Our Latest Obsessions

The 1998 indie movie from Darren Aronofsky has more to say about today than ever

The great 1998 indie movie “Pi,” by now master-director Darren Aronofsky, begins this way, with the mathematician Max stating his assumptions about the universe:

Mathematics is the language of nature.

Everything around us can be represented and understood from numbers.

If you graph the numbers of any system, patterns emerge. Therefore, there are patterns everywhere in nature.

In the movie, Max’s obsession matches up with his attempt to predict the stock market, not so much to get rich as to do it for the sake of doing it.

And later in the film, Max’s pursuit of numbers hidden in nature means he’s trying to find God, which is a 216-digit code, the supposed key to everything.

In paranoid-thriller style, he’s chased by two groups obsessed with obtaining this number “key”: a non-descript Wall-Street group and a bunch of traditional religious Jews trying to usher in the Messianic age.

However, do you see anything in Max’s stated assumptions above that seems contemporary? That screams “2025!”?

On rewatching this three times this year, I did.

Boy, did I ever.

And that “anything” is the current age’s obsession with turning everything into numbers. In short, the Algorithmic Age of Reduction-to-Numbers.

Welcome to the mid-2020s!

The list of traditionally and inherently complicated subjects that get turned into numbers these days is endless. They include: your emotions, your teaching effectiveness, your love and marriage, your pain (“how would you rate your pain on a scale from one to ten?”), all artworks, your religious experience, your taste in food, your recreational experiences, your mental health (“in the last month, how depressed have you felt, on a scale from one to ten”).

And maybe also God and spirituality. (My church, somehow, has a star-rating on Google.)

This is the promise of the Enlightenment gone insane.

Except it doesn’t know it’s insane. There’s a fine-line between insanity and genius, the old Aristotelian observation that “Pi” repeats in dialogue. Max is either one or the other, maybe both.

“Pi” shows Max’s obsession taken to its limits, his attempt to find order in all things, to reduce everything to an understandable ordered system that can also be predicted by patterns. To do this, he uses his supercomputer Euclid, which he built himself.

Being about obsession with finding ultimate reality, which is hidden behind observable reality — the numbers or code behind all of nature — “Pi” does extraordinary work at depicting what that feels like.

In its best moments, it will annoy or even anger you. And I think that’s what the movie wants: you need to feel the angsty rage that the isolated Max feels.

Early on, Max observes a tree, one of the movie’s essential images. What do you see in this shot?

I see a tree. A psychologist might see a Rorschach test. A botanist might see a complex living creature. An astronomer might see the heavens in the negative space. An artist might see inspiration.

An obsessed mathematician with the assumptions of Max, however, might see the possibility of a pattern. This object hasn’t rendered up its true meaning, the mathematician might say, but with the right system by which to discern its true reality, it will.

That makes Max a kind of gnostic. He’s after secret knowledge that only a few might be able to possess. That might mean power and contorl, or at least the Wall-Street types and the Jewish groups after Max think so. Poor Max just wants to be the one to solve the puzzle, not dominate the world.

You know what else is in that image above? A Captcha pic. Also, an image to be analyzed in terms of chaos theory or for patterns.

I just inputted the image into ChatGPT, and it rather gladly tried to discern patterns and symbols in it! (E.g., “In the bottom-left quadrant, among the dense cluster of edges, I noticed a vertical shape paired with a circular edge that could pass for a distorted 9 or 6.”)

Nope, ChatGPT, try again!

Trying to find meaning in the wrong place, or to find a meaning by means of the wrong assumptions, is the problem with Max. His obsession is misplaced.

The movie, wisely, knows this. It moves towards an ending, via “Taxi Driver,” that’s among the most open-ended conclusions you will ever see.

Without spoiling that for you, the ending is almost infinite, with infinite meanings. You cannot contain it in numbers, patterns, or systems. ChatGPT will — I daresay — never be able to analyze and pin down the ending of “Pi.”

Which is one of the most glorious things about this film.

Before that ending, the movie depicts Max as an insular figure who could be social, even cosmopolitan. Living in Chinatown, Max has a Chinese girl knock on his door to ask him questions. His Indian neighbor gives him a samosa. She tells Max he needs a mother. Walking around NYC, Max could talk to any one of a million people.

However, wrapped up in his devices, Max remains singularly alone.

He pops pills to hopefully control his mental disorders, whichever ones he has (the movie is vague on this, though schizophrenia seems almost certain).

The movie places a pill-consuming montage showing Max’s need to regularly take his meds. This happens seven times, probably somehow a significant number in a movie obsessed with numbers.

Here “Pi” might also succeed in depicting what it’s like to be OCD, schizophrenic, and paranoid, or some combination of these and more. This is the type, the movie says, going after ultimate truth via mathematics. Max might be the stereotypical nerd, though highly damaged or traumatized.

Today, with mental illnesses or not, he could work in Silicon Valley, designing algorithms for your favorite Internet-dating app. These are the matchmakers of the Algorithmic Age.

For love, to these people, is a discernable pattern of numbers.

In too many ways, what I just described about “Pi” could be typical, probably stereotypical. It *was* in 1998. The imagery and themes come right out of paranoid thrillers of the time that you may know: “The Truman Show,” “Dark City,” “Enemy of the State,” and most notably “The Matrix.”

I note that pill-popping, in “The Matrix,” is a necessary good. Choose red or blue, though. But “Pi” has a scene that rejects the pills, a solution of a kind to Max’s mad obsession.

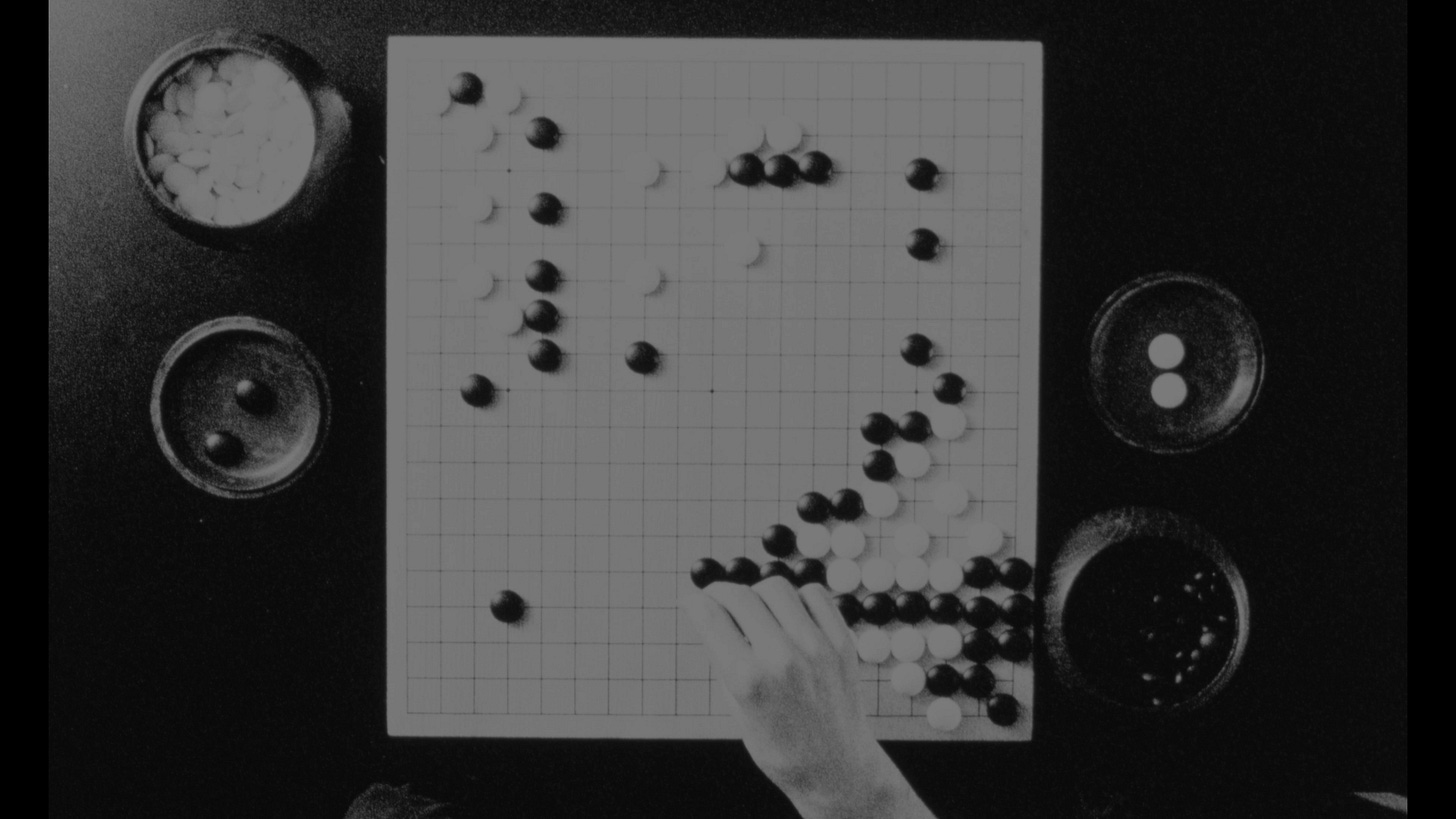

However, as an indie movie, “Pi” is no slick production like “The Matrix.” It’s black-and-white color scheme literalizes Max’s reductive obsessions. Fittingly, he plays “Go” and constantly observes stock tickers, both featuring black and white circles that he believes must reveal patterns.

Like the image of the tree above, what do you see here? Max’s teacher — named Sol Robeson — sees a peaceful chaos. However, Max believes that these patterns converge to a knowable order, which he must find.

I see games involving circles, the stock market information and “Go” itself. I also see a social and economic aspect to each. And I see philosophical questions galore.

Like most Aronofsky movies, “Pi” turns theological. Obsession ruins Max. He needs to see peace. This is figured — an image that Aronofsky has always embraced — by fades or quick cuts to an all-white screen.

In “Pi,” they are accompanied sonically by Buddhist-like “oms.” To fit in with that Max shaves his head, possibly like the prophet Ezekiel or like Buddhist monks.

Or the head-shaving is ala Travis Bickle in “Taxi Driver”? ‘

Will the isolated, frustrated Max turn violent ala Bickle, or will he achieve Zen-like peace? Are those two halves of the same self, like the game “Go”?

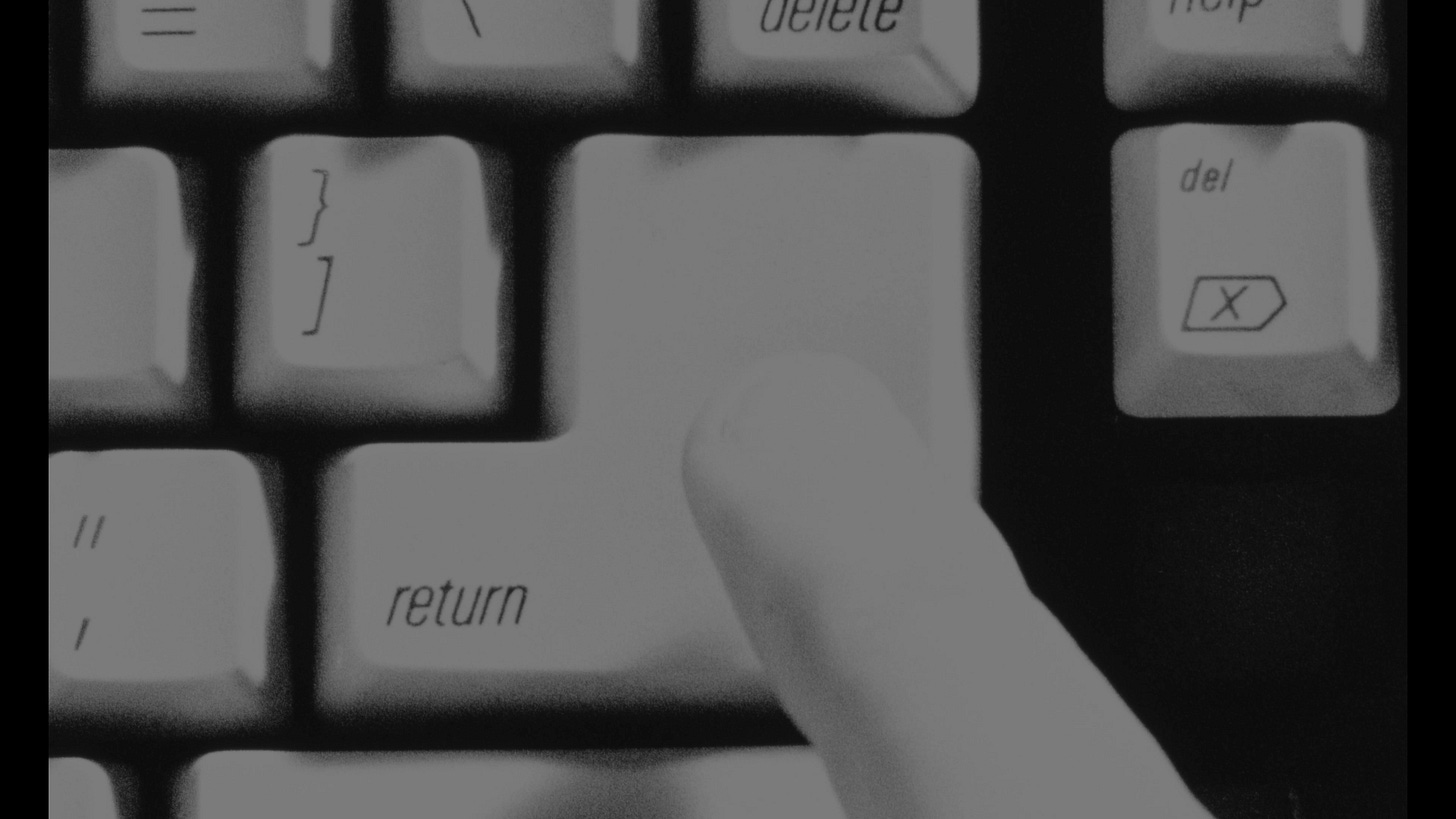

No movie more actively invites numerological analysis than “Pi.” Two songs in its score are named after geometric equations. One scene actively teaches viewers that ancient Hebrew may be a secret numbers-code. Max seeks a numbers printout, striking the “return” key to create numbers, while claiming that “there is a pattern.”

Visually, as with the repeated striking of the “Return” key, the movie *returns* to various images so many times that it would seem that “there is a pattern.”

If Max watched this movie, he would double-down on his obsession with finding secret numbers behind the images.

I resist this temptation completely.

It’s a spiritual movie, and finding numerical order in everything might well be the ultimate folly. It’s best to let “Pi” be “Pi,” as open-ended in the end as it wants to be.

“There is a pattern.” This today I hear about language, music, drawings and images, human mating habits, religious experiences — you name it.

If that’s so, it’s all reducible to an algorithm, which becomes the god of the system you are imprisoned within. I can predict your behavior if I just observe you and write the right mathematical formula that explains the patterns, or so I’m told.

We are now at a bunch of delightful possibilities — predictive policing, for example.

Max’s views represent a current norm, one with billions of dollars behind it to promote its worth, use, and prevalence. This I see in my X feed, which is created by my habits and the supposed pattern-recognition based on those habits. I’ve been gamed. I’m a black or white circle in a game of “Go.”

Early in the film, Max tells a story about staring in the sun when he’s six years old. He defies his mother’s commands not to look into the sun. This damages him, or enlightens him, or both.

“Pi” lets us stare into this bright light, too. What patterns do you see here? What numbers are behind the image? How would you rate your experience of this image, from a scale from 1 to 10?

These, of course, are entirely the wrong questions.